Louis Kahn, the modernist architect and the man behind the myth

We chart the life and work of Louis Kahn, one of the 20th century’s most prominent modernists and a revered professional; yet his personal life meant he was also an architectural enigma

The first impression of Louis Kahn’s architecture is one of timelessness: monumental, monolithic forms in concrete, brick and stone. There is an ethereal, almost spiritual quality to his buildings that, from California to Bangladesh, remain touchstones of 20th-century design and a key chapter in the world's modernist architecture journey.

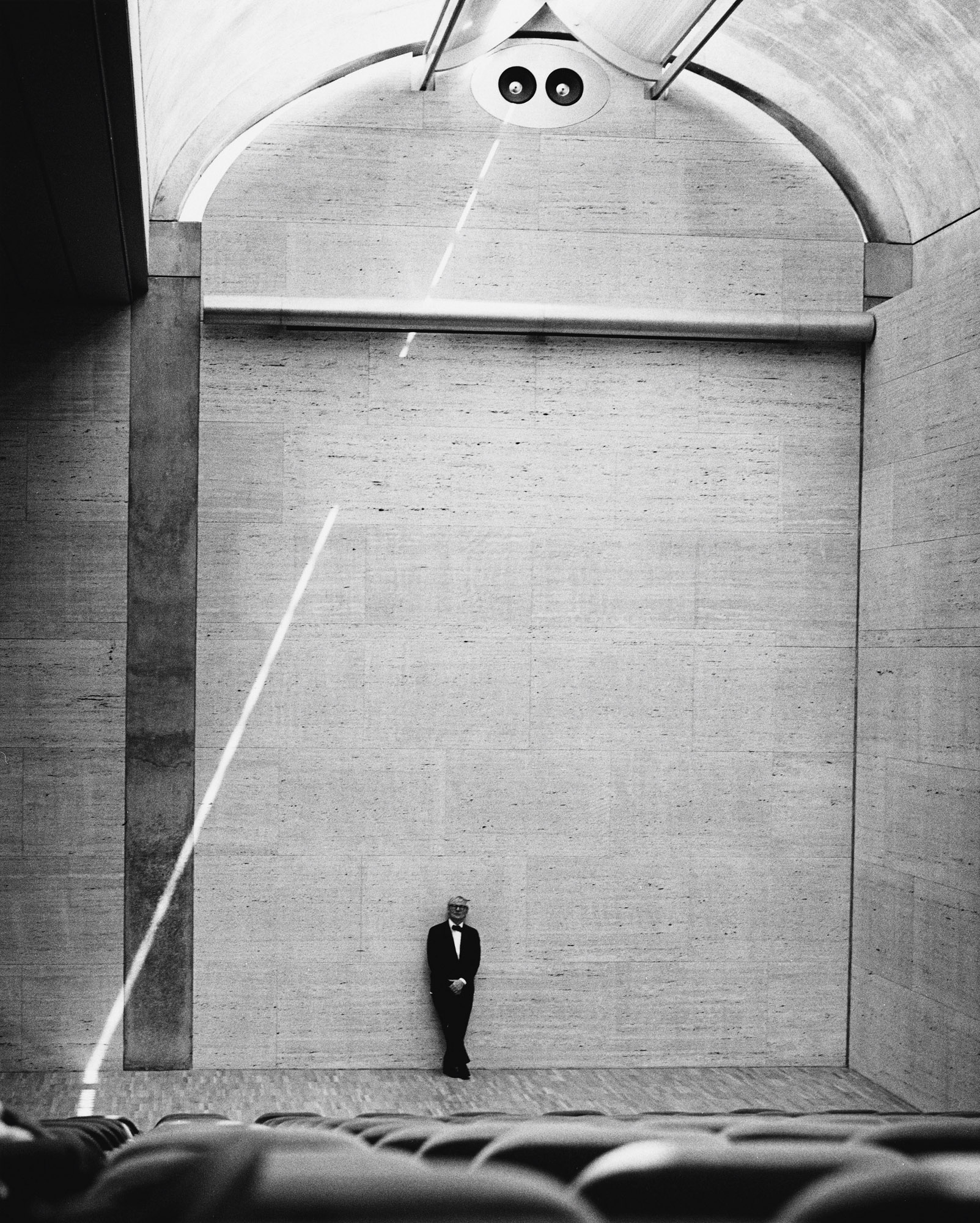

Louis Kahn, photographed in the auditorium of the Kimbell Art Museum in 1972. The legacy of the modernist architect lives on to inspire a new generation – Louis I Kahn: The Last Notebook, edited by Sue Ann Kahn, was released in April 2024

Louis Kahn: a modernist myth

From small-scale, sole practitioners to the world-renowned starchitects, architects around the world have been inspired by Kahn’s work for its modernist artistry and design precision, at once laudable and almost unattainable. Yet the man behind the myth lived a life marked by struggle, one that was financially precarious and personally fractured. The contrast between the serenity of his work and the turbulence of his existence continues to shape Kahn’s legacy.

Louis Kahn: a brief history

Itze-Leib Schmuilowsky was born in 1901 into a poor Jewish family in Kuressaare on the remote western Estonian island of Saaremaa, then part of the Russian Empire. At the age of three, the boy, captivated by the light of coal burning in the stove, put some glowing lumps into his apron, which immediately caught fire, badly burning his face.

The resulting scars would disfigure Louis Isadore Kahn (the name officially given to Itze-Leib in 1915, some years after the family had moved to Philadelphia) for the rest of his life. Poverty continued into Kahn’s early years growing up in America, where, unable to afford pencils, he would make his own charcoal sticks to allow him to earn a little money from drawing. Despite having notable artistic talents, Kahn turned down a fully paid scholarship to study art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, choosing to take numerous jobs to self-fund an architecture degree at the same institution.

Louis Kahn, circa 1970

You may ask what bearing Kahn’s early struggles have on understanding his architecture. Yet only by recognising his hardships and the fact that it was not until he was in his fifties that he began producing the works that defined his portfolio, can we grasp the depth of his genius and the weight of his legacy. After graduating in 1924, he built a steady if unremarkable career, first as a draftsman for a Philadelphia city architect and later in several prominent firms there.

In 1932, at the height of the Depression, he co-founded the Architectural Research Group with Dominique Berninger, an ambitious attempt to pursue socially responsive design. Unfortunately, commissions were scarce, and the venture soon dissolved. For two decades, Kahn laboured largely in obscurity, producing modest projects while supporting himself through teaching, where he began to articulate architecture on his own terms. For him, architecture was fundamentally the search for order, light, and meaning.

A turning point

A decisive turning point in Kahn's career came in 1950, when a residency at the American Academy in Rome confronted him with the grandeur of antiquity. Among the ruins of the Baths of Caracalla and the Pantheon, he absorbed a sense of monumentality that transformed his vision. Soon after, Kahn’s design for the Yale University Art Gallery (1951-53) announced the arrival of his mature voice – a fusion of modern construction and timeless gravitas, and the first of the great works that would secure his legacy.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Yale University Art Gallery

These buildings chart the emergence of one of modernism’s most distinctive voices. The Richards Medical Research Laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania (1957-61) spoke a new language of articulated forms. The Salk Institute in La Jolla (1959-65) was a crystal-clear distillation of his vision, while the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth (1966-72) demonstrated his unrivalled mastery of light. Perhaps most ambitious of all, the Jatiyo Sangsad Bhaban in Dhaka (1962-83) gave architectural form to a nation’s democratic aspirations. Across these projects, Kahn’s respect for materials and his belief that light was 'the giver of all presences' shaped buildings that stand today as testaments to modern architectural achievement.

Jatiyo Sangsad Bhaban in Dhaka

And yet Louis Kahn remains an enigma, one where the misty solemnity of a clutch of beautiful works belies the turbulence of his life. Kahn was frequently in debt and relied on teaching to sustain his practice. His personal life was infamously fractured. He married once, but fathered three children with three different women. In the Oscar-nominated documentary My Architect: A Son’s Journey (2003), his son Nathaniel captures this complexity with candour, setting the absence of the father against the grandeur of the architect. That grandeur endures because Kahn pursued the most elemental of questions: 'What does a building want to be?' Footage captures him asking his students this in the film.

His life ended in 1974, at the age of 73. He died of a heart attack in the restrooms of New York’s Penn Station, returning from a trip to India. The humanity of his life and death makes his creations all the more allegorical.

An origin story

The location of the proposed Louis Kahn Centre on the island of Saaremaa

On 12 September 2025, the Louis Kahn Estonia Foundation hosted a day-long international seminar at the Bishop’s Castle in Kuressaare, the place of Kahn’s birth. Guest speakers presented the Estonian Government-backed initiative to establish the Louis Kahn Centre on the island of Saaremaa. At the centre’s core will be a permanent exhibition, library and archive showcasing Kahn’s work and philosophy.

9 key buildings

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven (1951-53)

Kahn’s first major building revealed a new architectural voice. The gallery introduced his hallmark clarity through exposed concrete, brick, and a pioneering tetrahedral ceiling that combined structural efficiency with sculptural presence. It provided naturally lit, flexible galleries that broke from sterile modernist templates. Modest in scale yet radical in intent, it established Kahn as a thinker committed to material honesty and spatial dignity. The commission, awarded while he was teaching at Yale, gave him the platform to explore ideas that would mature into the monumental works of his later career.

Richards Medical Research Laboratories, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (1957-61)

A turning point in laboratory design, Richards Laboratories separated service towers from research spaces, allowing flexible interiors filled with light. Its bold concrete towers became a defining image of Kahn’s search for 'served' and 'servant' spaces, terms he coined to describe the hierarchy of functions in architecture. Though controversial at the time, and far from loved to this day, the building demonstrates a major gear shift for Kahn.

Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla (1959-65)

Jonas Salk invited Kahn to design a campus that would inspire scientific discovery. The result is an oceanside, modernist marvel: paired concrete laboratory wings flanking a travertine plaza, where a thin channel of water draws the eye to the Pacific horizon. Kahn combined functional laboratories with contemplative space, embodying his conviction that science, like architecture, seeks truth. The Salk’s blend of utility, serenity, and monumentality continues to make it one of the most revered research environments in the world, admired as much for its spiritual resonance as its technical performance.

Phillips Exeter Academy Library, Exeter, New Hampshire (1965-72)

The Phillips Exeter Academy, as featured in 'Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture', a Design Museum exhibition in London in 2014

Widely considered one of the finest libraries of the modern era, this one at Phillips Exeter Academy exemplifies Kahn’s ability to create order through clarity. A massive brick cube contains a luminous central atrium framed by soaring concrete crossbeams, surrounded by concentric rings of study spaces. Students encounter books in intimate carrels before ascending to the cathedral-like core. Function, ritual, and poetry align seamlessly.

Norman Fisher House, Hatboro, Pennsylvania (1960-67)

This modest private residence demonstrates Kahn’s mastery of scale at the domestic level. Two wood-slatted brick cubes, linked by a central stair hall, form a composed yet complex plan. Large windows create an interplay of light and privacy, while careful detailing lends gravity to a small structure. The Fisher House distills Kahn’s monumental language into an intimate family dwelling.

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas (1966-72)

The Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, where an extension, the Renzo Piano Pavilion, was added to in 2013

Kahn’s Texan masterpiece is revered for its flawless integration of art, light, and structure. A sequence of cycloid vaults houses galleries flooded with soft, natural light, filtered through ingenious skylights and reflectors. The architecture elevates the experience of viewing art without distraction or spectacle. Commissioned after a competitive selection process, the Kimbell affirmed Kahn’s international standing. Its blend of restraint and richness remains unmatched, setting a benchmark for museum design that continues to influence architects around the world.

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven (1969-74)

After years of restoration, The Yale Center for British Art, Louis Kahn’s final project, reopened in spring 2025

Kahn’s last completed work, the Yale Center for British Art reflects a lifetime of refinement. Behind a restrained concrete and steel exterior lies a sequence of galleries organised with luminous clarity. Natural light animates the spaces, while oak panelling adds warmth. Completed after the architect’s death (it opened in 1977), it stands across the street from his first gallery at Yale – a fitting bookend to his career.

Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad (1962-74)

The brick volumes of the Ahmedabad dormitories by Louis Kahn at the Indian Institute of Management

Invited by Vikram Sarabhai, one of India’s leading industrialists, Kahn created a campus of brick forms and geometric rigour. Monumental arches, voids, and corridors foster a sense of community while shielding interiors from the harsh climate. The design blends modern structural thought with the spatial traditions of India, producing a place both practical and profoundly symbolic. Though incomplete at his death, the campus remains one of the most influential works of educational architecture in South Asia.

Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban (National Assembly), Dhaka, Bangladesh (1962–83)

Commissioned by Pakistan but completed for independent Bangladesh, this vast parliamentary complex epitomises Kahn’s belief that architecture can embody civic ideals. Colossal concrete walls are pierced with geometric openings, creating dramatic interiors filled with light and shadow. The Assembly Hall, ringed by reflecting pools, combines solemnity with openness. Construction spanned decades after Kahn’s death and was a monumental national endeavour for Bangladesh, then one of the poorest countries in the world. Today it stands not only as his magnum opus but as a symbol of national identity, demonstrating architecture’s capacity to represent democracy itself.

David is a writer and podcaster working (not exclusively) in the fields of architecture and design. He has contributed to Wallpaper since 2022 when he wrote about the late, postmodernist architect and founder of the Venice Architecture Biennale - Paolo Portoghesi reporting from his home outside Rome. In 2024, David launched Arganto - Gabriele Devecchi Between Art & Design, a podcast exploring the life and legacy of this Milanese silversmith and design polymath.

-

Tour Cano House, a Los Angeles home like no other, full of colour and quirk

Tour Cano House, a Los Angeles home like no other, full of colour and quirkCano House is a case study for tranquil city living, cantilevering cleverly over a steep site in LA’s Mount Washington and fusing California modernism with contemporary flair

-

At Dubai Watch Week, brands unveil the last new releases of the year

At Dubai Watch Week, brands unveil the last new releases of the yearBrands including Chopard, Louis Vuitton, Van Cleef & Arpels present new watches at Dubai Watch Week

-

Wes Anderson at the Design Museum celebrates an obsessive attention to detail

Wes Anderson at the Design Museum celebrates an obsessive attention to detail‘Wes Anderson: The Archives’ pays tribute to the American film director’s career – expect props and puppets aplenty in this comprehensive London retrospective

-

Tour Cano House, a Los Angeles home like no other, full of colour and quirk

Tour Cano House, a Los Angeles home like no other, full of colour and quirkCano House is a case study for tranquil city living, cantilevering cleverly over a steep site in LA’s Mount Washington and fusing California modernism with contemporary flair

-

This modernist home, designed by a disciple of Le Corbusier, is on the market

This modernist home, designed by a disciple of Le Corbusier, is on the marketAndré Wogenscky was a long-time collaborator and chief assistant of Le Corbusier; he built this home, a case study for post-war modernism, in 1957

-

An ocean-facing Montauk house is 'a coming-of-age, a celebration, a lair'

An ocean-facing Montauk house is 'a coming-of-age, a celebration, a lair'A Montauk house on Hither Hills, designed by Hampton architects Oza Sabbeth, is wrapped in timber and connects its residents with the ocean

-

With a freshly expanded arts centre at Dartmouth College, Snøhetta brings levity to the Ivy League

With a freshly expanded arts centre at Dartmouth College, Snøhetta brings levity to the Ivy LeagueThe revamped Hopkins Center for the Arts – a prototype for the Met Opera house in New York –has unveiled its gleaming new update

-

From Bauhaus to outhouse: Walter Gropius’ Massachusetts home seeks a design for a new public toilet

From Bauhaus to outhouse: Walter Gropius’ Massachusetts home seeks a design for a new public toiletFor years, visitors to the Gropius House had to contend with an outdoor porta loo. A new architecture competition is betting the design community is flush with solutions

-

Robert Stone’s new desert house provokes with a radical take on site-specific architecture

Robert Stone’s new desert house provokes with a radical take on site-specific architectureA new desert house in Palm Springs, ‘Dreamer / Lil’ Dreamer’, perfectly exemplifies its architect’s sensibility and unconventional, conceptual approach

-

New York's iconic Breuer Building is now Sotheby's global headquarters. Here's a first look

New York's iconic Breuer Building is now Sotheby's global headquarters. Here's a first lookHerzog & de Meuron implemented a ‘light touch’ in bringing this Manhattan landmark back to life

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthFrom Malibu beach pads to cosy cabins blanketed in snow, Wallpaper* has featured some incredible homes this month. We profile our favourites below